#8 What do the election results mean for India's fishers

On 4th June 2024, India, the world's largest democracy, chose not a single party in majority. Out of a total of 543 parliamentary constituencies, it handed over 292 seats to the right-wing National Democratic Alliance led by Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) and 234 seats to Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), a big tent multi-party alliance of several political parties in India, including the left Indian National Congress (INC)

The 18th general election of India was remarkable on several counts.

After a decade of enjoying singular control over the state, the right-wing Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) has been forced to form a government in coalition with Bihar's Janata Dal (United) (JDU) headed by Nitish Kumar and Andhra Pradesh's Telegu Desam Party (TDP) headed by Chandrababu Naidu, both historically known for their secular ideologies, amongst several other political parties. Their support is crucial for the NDA to stay in power. After winning singular majority for two consecutive terms, being forced to form a coalition with regional parties is not a good win for the Narendra Modi-led BJP. One senses a defeat in this win.

Similarly, after a decade of nearly-crushed resistance, a seemingly strong, united opposition has emerged in the form of INDI Alliance. Even though they failed to win enough seats to form a government, ever since formally declaring an opposition, INDIA has already held a press conference demanding an enquiry into the misleading exit polls, and the crashing of stock markets on the day the election results were announced, leading to a loss of over INR 30 lakh crore. One senses a win in this defeat.

A brief analysis

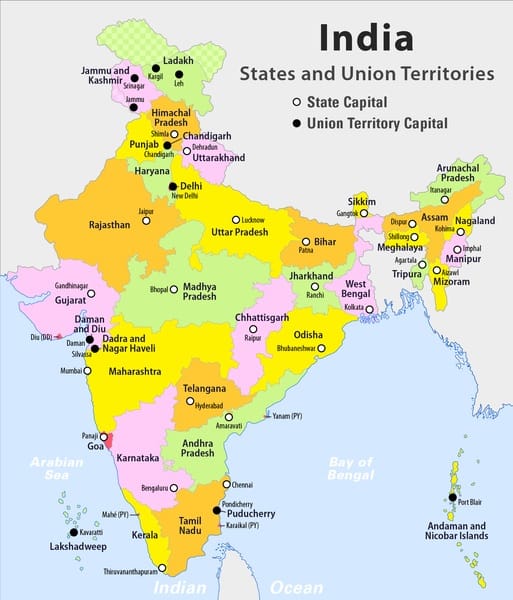

India's nine coastal states, two union territories and two island territories have a total of 91 coastal parliamentary constituencies. Out of these NDA won 49 seats, and the INDI Alliance won 39 seats.

West Bengal brought back the All India Trinamool Congress, a regional party of the state that is also in alliance with INDIA. The coastal region of the state has been in the news for the proposed deep-sea Adani port in Tajpur, and for the upcoming missile-testing center in Junput, an area known for its dry-fishing activity and where over 6000 fishers reside.

Odisha, which has been governed uninterrupted by regional party Biju Janata Dal (BJD) for the last 24 years, flipped over to bring BJP to power in a landslide win. Coastal Odisha, which has historically been a BJD favorite, brought the BJP to victory. Environmental publication Down To Earth reports that the marine fishers of the state have been frustrated over the state government's inaction in addressing their longstanding demands for fuel subsidy, regular dredging at harbours, and inclusion in social security schemes. They hope a change in government will mitigate their hardships.

In Andhra Pradesh, the Telegu Desam Party (TDP), a regional party and an alliance of the NDA, emerged victorious. Andhra Pradesh, one of the largest producers and exporters of farmed shrimp in the country, was in the news recently over an exposé of labor violations in the shrimp industry. Reports found that the workers live in 'dangerous and abusive' conditions. While this created a huge dent for India in the international markets, experts say that this was not a topic of discussion during the elections.

Tamil Nadu chose Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), the current ruling party of the state and an alliance of INDIA. Kerala, which has been in the news over the controversial Adani port at Vizhinjam, the INC-led United Development Front (UDF) won. For the first time, BJP also won a seat in the Thrissur constituency of the state.

In Goa which has two parliamentary constituencies, both the BJP and the INC got a seat each. In Maharashtra, Uddhav Thakeray's Shiv Sena, an alliance of INDIA won. Both Karnataka and Gujarat were swept up by the BJP. Lakshadweep voted for the INC while the Andamans and Nicobar island voted BJP into power.

So what does this all mean?

The fisheries policies of India have continuously evolved since the 1950s. In the beginning, fisheries was recognized for its contribution towards food security, employment, and income generation. By the 60s, the intention of export-oriented production of marine fisheries was clear in the way policies were made. Efforts were made to upgrade fisheries technology to intensify exploitation of marine resources. The MPEDA (Marine Products Export Development Authority) was formed in 1972. The 70s and 80s were marked by mechanization of the fisheries sector, introduction of trawlers and supporting infrastructure. The 90s and 00s were marked by a boom in aquaculture.

No matter the party at the center, the fisheries sector has always been looked at from the point of view of exploitation of resources.

Since 2014, with a single-party rule, the BJP-led government, furthered this intention of investment-export-production oriented fisheries. For the first time, in 2019, fisheries moved from being a department in the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers' Welfare towards becoming a ministry of its own – Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying.

The Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana (PMMSY) scheme was introduced on 2020, announcing a financial package 20,000 crore for the growth of the fisheries sector. The National Fisheries Policy, 2020 aims towards a production-driven, export-oriented, technology aided model of growth for the sector. The Sagarmala Project, established in 2015 clearly directs the idea that port-led development is the future of the country, emphasising on the privatisation of ports, building more infrastructure to connect the hinterland to the sea for ease of movement of cargo, expanding existing ports and constructing new ones, encouraging coastal shipping and coastal tourism. The Coastal Regulation Zone, 2019, has undergone 35 modifications, and the latest notification allows constructions closer to the high tide line, showing preference of ease of doing business over protection of ecology. The Coastal Aquaculture Authority [Amendment] Bill 2023 has opened the coast for aquaculture farms – shrimp, seaweed, cage culture and the allied infrastructure [hatcheries and breeding centers] to flourish without restrictions of any coastal regulations.

The policies and initiatives recognise the importance of fisheries.

But the fisher, and their well-being, is largely forgotten in this 'growth' story.

Where is fisher well-being in the coastline's growth story?

The Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations formulated the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication in 2014. Also known as the SSF Guidelines, this is the first international instrument dedicated entirely to the small-scale fisher. The guidelines emphasise adoption of a human rights-based approach and advocate participation of fishing communities in the decision-making processes, while they assume responsibility for sustainable use of fishery resources.

The election manifestos of two leading national parties – the BJP and the INC, do not mention fisher well-being. Both manifestos indicate policies that thrust on production, technological upgradation, aquaculture promotion, and market promotion.

A 2024 paper called Making Sense of the Legal Policy Frameworks Governing Small-Scale Fisheries in India explains that until 2017, the development policies for the fisheries sector were formed under five-year plans and financed through both budgetary and plan allocations. But with the closure of the Planning Commission in 2014, the central funding is limited to budgetary allocation under the union budget. This has further restricted social security provision for the fishers' well being, again prioritizing Blue Economy initiatives at both the state and federal level.

When the institutional policy framework itself incentivizes mechanized and investment intensive fishing practice, when port-led development model of growth is favoured, when export-oriented fish production is given a boost, then how does it matter which government comes to power? The INC has been rallying against Adani Ports, but not a peep against the Sagarmala Project, for example.

Perhaps there is a glimmer of hope in the fact that the institution today is governed by a coalition. That it is an alliance of different ideologies coming together – both in the governing, and in the opposition. Perhaps there will be more room for discussion, debate and deliberation in framing policies. Perhaps the protests against displacement of coastal communities, against unbated destruction of ecosystems will lead to actual liberation. Perhaps. Whatever happens, we will be watching. Stay tuned.

Note: The paper 'Making Sense of the Legal Policy Frameworks Governing Small-Scale Fisheries in India' is a chapter from the book Implementation of the Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines: A Legal and Policy Scan (pp. 279-298) (2024) by Pradhan, S. K., Nair, T. S., & Nayak, P. K, published by Springer Nature Switzerland.