#16 The history of farmed shrimp in India

By Siddharth Chakravarty

This is a two-part series written by Siddharth Chakravarty, a nerdy shrimp researcher, explaining the entire production line of the tiny, mighty farmed shrimp. This is part one, and a part of our overall ongoing series called The Story of Shrimp

Before this explainer gets nerdy and technical, let us start by looking at the world’s map. In the map below, on the very left is the Gulf of Mexico, a marginal sea under the North American continent. At the very right, along the same latitude, is India. And what connects the two ends of this map for this story, across many seas and oceans, is the production line of farmed shrimp. A shrimp species—the Pacific White Shrimp—native to the Gulf of Mexico, has in its millennial timeline become the poster child of the shrimp farming industry.

On a world tour across laboratories, hatcheries, farms, processing units, cold storages, container ships, and through the labour of a swathe of social actors, this shrimp makes its way from the Americas to India and back to the Americas to fill the appetites of American consumers. Not only in India, this species of shrimp is the world’s most favoured farmed shrimp species. Just like the broiler chicken, shrimp has become a versatile, accessible, affordable and easy to cook seafood option across the country. Since India is one of the world’s biggest producers of shrimp, we’re going to take a look at the industry here.

Professing love for shrimp

India’s policy and administrative planners have had a deep fascination with shrimp. In the early days of Independence in the 1960s, the marine fishing policies quickly shifted from their welfarist origin to a commercial, export-oriented one aimed at meeting the growing appetite for tropical shrimp. This shift was likely influenced by a combination of factors – one, the dominant global development model that pressured planners to orient export policy to increase foreign exchange earning through the export of primary products and two, demands from domestic entities interested in capitalising on the access to global market. Most of the contemporary shrimp corporations are domestic entities, some of who share their origins to this era.

Bottom trawling, particularly on the west coast of India, was very successful in the 1960s-1990s decades. It catapulted India into one of the world's biggest exporters of shrimp, particularly to Japan and the European Union states. However, alongside this, there have continuously been attempts to grow shrimp in controlled environments and domesticate wild shrimp stocks for spawning purposes.

Controlled spawning is a key process in the domestication of wild stocks. Control over spawning allows for the hatchery-based reproduction of species which helps in the scaling up of production.

Documents from as early as the 1960s reveal Indian government scientists pondering over the right environmental conditions that would allow for shrimp to be grown in coastal areas and in the decades after, publishing manuals from their successful field trials. Very simply put, within the confines of a few indicators and with the demand in the lucrative overseas market growing, the farming of shrimp was considered to be more cost effective per kilogram of production and came with the possibilities of scaling production of select species that were in demand.

The boom and bust of the Black Tiger Prawn

The Black Tiger Prawn is a native species to India and landings through trawling gears have been feeding the high demand in export markets. In the 1980s, Andhra Pradesh emerged as the region where the farming of black tiger prawns took off. Initially mangrove lands, then estuarine and riverine lands, and finally paddy lands began to be converted to shrimp farms. The process usually requires the first three feet of soil to be dug out. The top fertile soil, which is sold to finance the excavation costs, is lined up as bunds along the border, resulting in a pond that is about 6-7 feet deep. By and large, the operational size of ponds in India today are less than an acre in size. Between the 1980s and the late 1990s, there was a prolific rise of farmed shrimp in the Krishna and Godavari districts, formerly the rice basket of the region, as more and more farmers began to convert their lands to shrimp ponds.

During these early decades of shrimp farming, the domestication of wild shrimp had not been achieved, and so the process of farming began by stocking the pond with wild juvenile shrimp which had been caught by local fishing communities in the sea. Some farmers even bypassed bans on the introduction of non-native animals and imported juveniles from Southeast Asia. In those days, there was very little environmental control on the inputs used in farming and effluents from the farming entering the sea. With the higher density of stocking shrimps in ponds, the uncontrolled environment and the use of wild broodstock, a big wave of illness mortality affected the shrimp farms in the region in the late 1990s.

Black out-White in

Such was the shock from the disease outbreak, that many of the shrimp producers were unable to recover their costs and many abandoned shrimp farming. Land under cultivation and productivity fell dramatically and the initial flourishing of the industry was in decline. Many shrimp processing firms and exporters were driven out of business during this period, with a corresponding decline in purchasing prices paid to producers. In 2005, trade laws kicked in and duties were applied to Indian shrimp bound for America, further affecting the production. It was around this time that a decade of slow growth, high disease prevalence and tight profit margins, spurred the transition away from the native Black Tiger Prawn to the exotic Pacific White Shrimp.

After the back-and-forth deliberations and trials on the shift, in 2009, the government of India paved the way for the Gulf of Mexico shrimp broodstock to be brought into the country and be grown in Indian farms. The rebounding of the industry has been nothing less than spectacular; as the graph below shows, the year-on-year growth line for the first decade after the introduction is nearly vertical. Alongside the increase in volume of farmed shrimp has been the rise of processing facilities, hatcheries, feed mills, medicine and other input firms, and a host of technical, scientific and extension services around shrimp farming. It is estimated that the shrimp industry currently employs, directly and indirectly, about 1 million people. India approximately produced a sixth of the world’s farmed shrimp in 2024, and shrimp exports dominate the country’s agri-food export basket.

While the production of shrimp increased tremendously, the area under cultivation has not increased correspondingly, indicating that most of the growth has come on existing lands but with a much higher productivity per acre. White legged shrimp live in a column of water which is the entire depth of the pond unlike the black tiger prawn which is bottom dwelling. Think of black tiger prawns in a 2D bottom model and white legged shrimp in a 3D distribution. Thus, in the same area of land, higher stocking of the Pacific White Shrimp is possible leading to higher productivity/acre. Second, white legged shrimp can thrive in a wider range of salinities, alkalinities and temperatures; this means that their farming can be carried out in a wider range of environments and periods. In Andhra Pradesh for example, white legged shrimp farming is a perennial activity over a wide range of soil-types and water sources. Third, the domestication of the wild shrimp allows for better control over the reproduction of the species, as well as the deliberate inducing of certain qualities to make them more resistant in farmed environments. Thus, even in intensive monocultures, compared to the black tiger prawn, the Pacific White Shrimp tends to be more resistant to certain diseases.

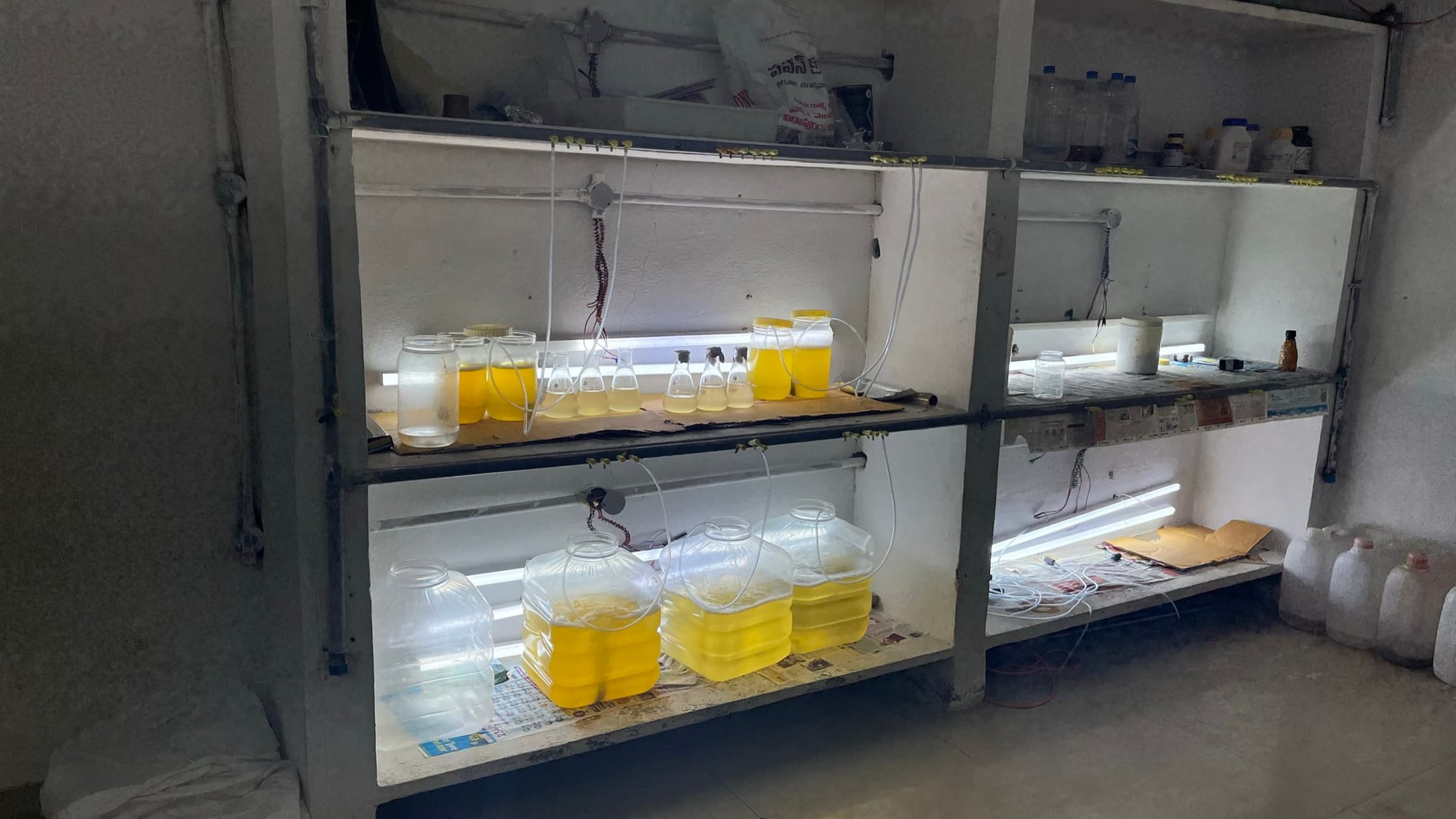

This is the end of Part 1. In Part 2, we will elaborate the entire production line of shrimp farming, hatching, processing and packaging.