#2 Cost of a Cyclone

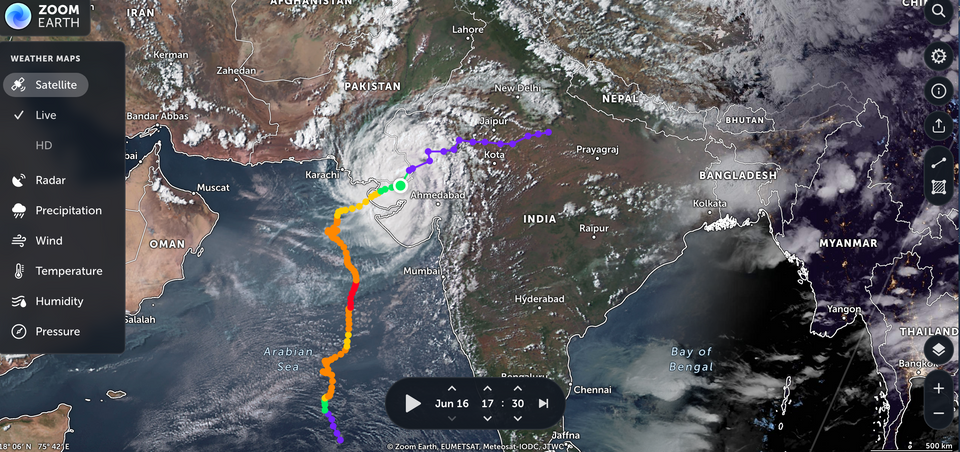

This June, India's west coast witnessed its longest cyclone since 1977. Starting on 6th June, a cyclonic depression in the central-eastern part of the Arabian sea slowly evolved into a cyclonic storm named Biparjoy [means 'disaster' in Bengali]. Over the course of nine days, on 15th June, it made landfall near Jakhau port, a fair weather port in the Kutch district of Gujarat. Three people died. Thousands of trees and electric poles were uprooted. Boats of fishers and jetties were damaged. A total of eight districts in the state were affected, including the ports of Jakhau, Okha, Mundra, Naliya and Mandvi.

While the state disaster management authority have made an initial assessment of the damage, the scale of damage for the fishing communities is yet to be properly examined. In Mangrol port for example, a fishing port that houses many big trawlers and purse seiners, the recently renovated jetty was damaged. "We have to send an official letter to the state fisheries department, explaining the extent of the damage, and only then would we be notified of compensation and reconstruction. But the problem is that this is the monsoon ban season and most people are not even here," a fisher based at the port told Fishy Waters over a phone conversation.

WHEN FISHING BAN CLASHES WITH CYCLONES

A similar issue has cropped up at Jakhau and Okha ports, where fishers tell us that boats have seen the maximum damage. A member of the Jakhau Boat Association, an outfit of boat owners in Jakhau, told Fishy Waters that around 15-20 boats seem to have been damaged by the cyclone — but the extent of damage can only be understood when one goes into the boats. Some will be broken, some will have water seeping in, some will have their outboard engine sputtering. "But most people are home, and home is in different villages. The authorities want everyone to report back with personal damages within the week. How are we supposed to do that?"

The monsoon fishing ban happens every year and lasts for 61 days – from April 15 to June 14 on the east coast and from June 1 to July 31 on the west (first and last dates included). In this time, the Centre uniformly bans fishing in the country’s exclusive economic zone. States impose the ban within territorial waters. During this time, fishers and fishworkers head home, to their native regions. The docks are mostly empty. It is only when they return to work can they examine their boats. Okha, which according to several fisher unions has faced the maximum damage [at least 50-60 boats] has a similar problem. "There are so many boats here already, its a natural harbour so boats are kept quite close to each other," Sattar Bharucho, a fisher based in Okha told us. "The high speed winds clashed a number of boats together and they broke. But the boat owners are not here. They will come back only when the season starts," he said.

The Jakhau port witnessed a number of demolitions of "illegal structures" last October. The structures included a marketplace and a number of trader shops. Fishers told us that the number of boats reduced from a thousand to 522. "All the big trawlers and exporters have moved away, and only small boat owners are here," Abdullasha Pirzada, president of Jakhau Bandar Fishermen and Boat Association told us. With this demolition, only a landing centre remained, where fishers can land and sort their fish, and are forced to sell the fish as soon as it lands, thereby giving them no control of the price.

COMPENSATIONS

Tropical cyclones have been battering India’s coasts with increasing frequency. Heavy rains and localised depressions in the sea add to reasons why fishing days have become fewer. The pandemic-induced lockdown exacerbated the crisis in 2020, directly affecting the supply chain and the livelihood of fishers and fishery-workers. In this time, the marine fisheries sector lost Rs 6,838 crore a month, according to a report by the Central Institute of Fishing Technology.

A fisher spends a minimum of a lakh on a medium-sized boat. The bigger its size and the more sophisticated its mechanics, the higher the price. When a cyclone destroys the boat, the state government is mandated to provide a compensation for the damage. But compensation is never nearly enough.

B. Kotesu, a fisher in Sonapur, in Odisha’s Ganjam district, for over 25 years. When Cyclone Phailin assailed Odisha in 2013, it destroyed B. Kotesu's, a fisher based in Ganjam district, small, 13-horsepower boat and his nets. The state of Odisha paid him a compensation of Rs 8,500 for Phailin’s damage

Kotesu took a loan of Rs 5 lakh from a local moneylender and bought another boat in partnership with a friend. But the interest piled up faster than he could keep up. He sold his share of the boat, and has since been working on another friend’s nine-horsepower vessel.

When Cyclone Tauktae barrelled through the west coast in May 2021, 70 boats were completely damaged on Madh Island, a coastal village near Mumbai, Maharashtra alone, according to Kiran Koli, general secretary of the Maharashtra Machhimar Kruti Samiti, a fishers’ union in Madh Island. Each fisher received Rs 25,000 as compensation. Each boat had cost Rs 25 lakh.