#3 India's fixation with shrimp - a policy perspective

Hola! Welcome to the third edition of Fishy Waters. This month, we want to spend some time unpacking shrimp – a tiny crustacean that has had India's fisheries policy and export market wrapped around its petite, pink shell since the 1950s.

Did you know India is one of the largest producers and exporters of shrimp in the world? This post attempts to explain how policy shifts have ensured that shrimp production stays at the top of the game.

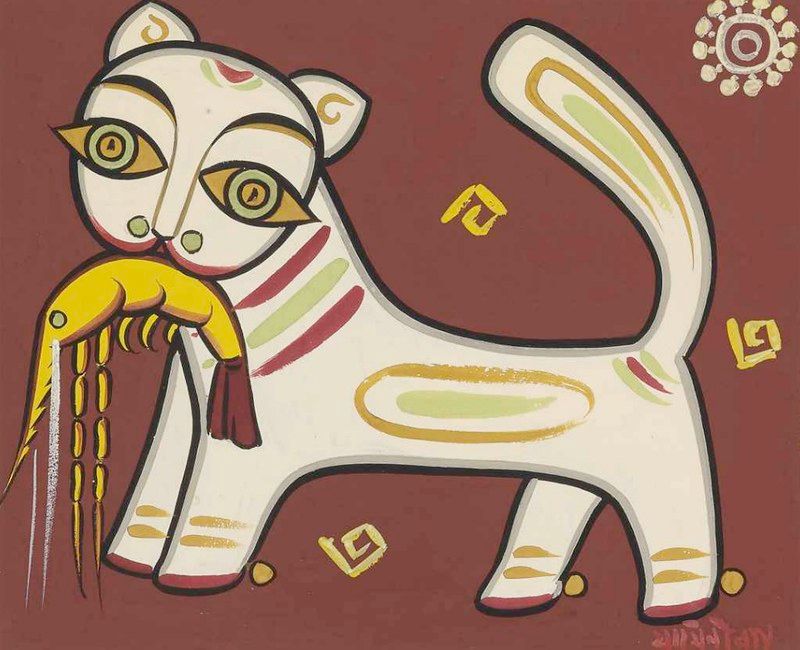

Shrimp, also often interchangeable with prawn in contemporary language, is a form of shellfish with an exoskeleton and ten legs. It has an elongated body, a narrow muscular tail, long whiskers and slender legs. A widespread, abundant specie, it is found in a range of habitats – from the seafloor on most coasts and estuaries to rivers and lakes. They live from one to seven years, and are often solitary. They organise in groups (schools) during the spawning season. They form food for a number of creatures – fish, whales as well as humans.

While the global history of shrimp as a food commodity of importance dates back to an ancient era, in India, shrimp became of commercial importance with the introduction of the Indo-Norwegian project in the 1950s. Under a tripartite agreement between the United Nations, the Government of Norway and the Government of India, wherein it was said that "that the Government of Norway will assist the Government of India in carrying out a programme of development Projects to contribute to the furtherance of the economic and social welfare of the people of India". Through a set of these development programmes, mechanised trawl fishery was introduced in India for the first time in Kerala. Shrimp is primarily caught through trawl fishing. A trawl net is a heavily weighted net kept on the seafloor, and is then dragged by boats, essentially sweeping the ocean floor, taking everything with it. It is considered to be one of the most destructive forms of fishing because of the high number of incidental by-catch. The seabed is swept clean.

A rise in the demand for shrimp from Japan, Western Europe and the USA led to the development of mechanised fishing in India. Most shrimp caught was exported. This era was also the beginning of a divide amongst fishers. As mechanisation became more popular and the international demand for shrimp continued to rise, the Indian government encouraged private investment, and private merchants entered the market, marginalising traditional fishers. The small-scale fishers and the mechanised boats were soon competing in the same waters, an unfair divide that has led to a number of rights-related issues today.

Industrial-scale coastal aquaculture became popular in India in 1980s and 90s. Aquaculture is like farming in water. It is a controlled cultivation of various aquatic organisms such as fish, molluscs, crustaceans, algae etc. Coastal aquaculture would be the controlled cultivation of aquatic organisms in brackish-water (water that is more saline than freshwater but less saline than seawater) areas near the coastline. In India, the traditional, small-scale practice of aquaculture involved cultivating shrimp and paddy in the same area on rotation, and has been dependent on the natural tidal flow of water bodies. But the commercial, large-scale practice of intensive coastal aquaculture gained prominence in the 80s and 90s thanks to the rising demand of shrimp for exports. A number of private companies and multi-national corporations began investing in shrimp farms. In intensive aquaculture, the aim is to produce maximum commodity using the least amount of water and land. Artificial ponds are set up with a high-density stocking rate. To maintain very crowded shrimp population and attain higher production efficiency, artificial feed, chemical additives and antibiotics are used. In many ways, in India, coastal aquaculture became synonymous with shrimp farming.

On 11th December 1996, in response to a public interest litigation filed by a S. Jagganathan, a farmer and activist based in Andhra Pradesh, the Supreme Court of India, passed a landmark judgement [(Writ Petition (Civil) No. 561 of 1994 (S. Jagannath v/s Union of India)], ordering an immediate regulation of the industry of shrimp farming in India. The petition was filed against the practice of intensive shrimp farming in Andhra Pradesh, stating that it brought about coastal pollution, leading to disease and lack of access to clean freshwater for fishers and farmers living in the vicinity. The judgement, by Justice Kuldip Singh, highlighted several risks and adverse environmental impacts of unregulated and intensive and semi-intensive coastal aquaculture. It ordered that since shrimp farming is an 'industry' it is a prohibited activity in accordance with paragraph 2(1) of the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ), 1991. The CRZ was set up under Section 3 of the Environment Protection Act (EPA), 1986. According to this notification, coastal land upto 500m from the High Tide Line (HTL) and 100m along the banks of creeks, lagoons, backwaters and estuaries is subject to tidal fluctuations, and is called the CRZ. No industrial activity is allowed within this area. The judgement also ordered the setting up of an Authority under the EPA (1986), regulating the industry under the 'polluter pays principle'. The judgement also ordered the shut-down of all shrimp farms that came within the CRZ area.

But, the judgement did not go down well in practice. It was seen that most of the shrimp farms were present within the CRZ area, and a shut-down would result in major economic and livelihood loss. Therefore, in an attempt to overrule the CRZ rules, the Indian government proposed formulate an Act instead. The Coastal Aquaculture Authority Act, 2005 was set up. The act allowed all shrimp farms to function, retrospectively amending the CRZ Notification, 1991 to exclude coastal aquaculture from the list of prohibited activities. It also constituted the Coastal Aquaculture Authority.

The production of shrimp has increased manifold. In 2022, there are nearly 43,000 registered shrimp farms across the country's coastline. In 2021-2022, India produced just over a million tonne of shrimp worth 7 billion USD. Today, India is amongst the top five exporters of shrimp in the world, along with China, Indonesia, Thailand and Equador. And it intends to keep pushing for more.

In April this year, the central ministry of fisheries introduced a Coastal Aquaculture Authority (Amendment) Bill, 2023 in the Lok Sabha, which was referred to the Parliamentary Standing Committee of agriculture. The standing committee of agriculture released a 163-page report justifying the need for a new Act. Some of the proposed salient features are:

- While the 2005 Act allows shrimp farming within CRZ areas, it prohibits allied activity, such as the setting up of hatcheries and nucleus breeding centers. The amended bill removes these prohibitions for the allied activities, allowing shrimp infra to be set up within the no-development zone of CRZ areas.

- The Bill gives the Aquaculture Authority the power to regulate the environmental impact of shrimp farms set up standards for inputs and discharge of effluents from aquaculture units, and also to monitor and regulate units, inputs, and emissions.

- The Bill decriminalizes offences such as setting up an unregistered farm or hatchery, reducing the punishment to a temporary suspension.

- The Bill also brings cage culture, seaweed culture and mariculture as activities allowed within the CRZ area under the ambit of coastal aquaculture. Originally, this was limited to shrimp farms.

The proposed amendments have been set up keeping in mind the central government's idea of linear, extractive growth models of unending production and increasing export, both in terms of quantity and value. But there are a number of red flags in the bill, as it fails to address some crucial concerns.

- From Supreme Court's comprehensive judgement of 1996, it is fairly clear that industrial coastal aquaculture has an adverse impact on the environment, and therefore it had held that an authority must be established under the EPA, 1986 to protect the coastal environment from adverse effects of shrimp farming. Following such orders, the central government had established the Aquaculture Authority under the EPA, 1986. But Coastal Aquaculture Authority set up later under the 2005 Act comes under the Fisheries Ministry. Now in light of this, the question is – is the Ministry of Fisheries the most appropriate ministry to administer the law regulating the environmental aspects of coastal aquaculture? The Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying is responsible for promoting and developing inland and marine fisheries. Its objectives are likely to prioritise the aquaculture industry over protecting the coastal environment.

- The Bill does not mention the potentialities of disease outbreak, or precautions against it, or how to regulate in case a thing happens. In 2000s, there was a major virus outbreak in the indigenous variety of black tiger prawn, leading countries to ban India from exports. This was replaced by the pacific white shrimp, also called the Vannamei, which is currently being produced and exported. Given the erratic climatic conditions and the intensive load on soil and water, there is always a high chance of high pathogen load seeping into the land leading to a disease outbreak. A better protocol and preventative regulations are needed in light of this.

- The Bill allows allied shrimp farming activity, along with mariculture, seaweed farming and cage-culture within the prohibited CRZ areas, leading to a much higher potential for more intense coastal pollution, along with lack of freshwater access for fishers and farmers.

- Most importantly, the Bill has not taken into account the opinions of small-scale fishers, the most important stakeholders in the space. Small scale fishers and fisheries are at the center of the health of the ecosystem, therefore they need to be at the center of these matters, and their opinions need to be taken into consideration. When fishers have access to the waters, it means that the water is healthy, and the sea is healthy which is a larger public good. The fact that none of the small-scale fisher unions were asked to give a representation by the parliamentary standing committee, goes to show that the authorities at large simply do not want this kind of information. And what does that tell you about this governance then?

The National Platform for Small Scale Fishworkers, one of the most important unions for small-scale fishworkers in the country has released a statement, unequivocally opposing the Bill. They call it "one of the most grotesque onslaughts by the united force of political power and capital on the coastal environment as well as on the livelihoods of millions of small-scale fish workers and farmers."

The next few editions will be devoted to the burgeoning shrimp industry of India — who wins and who loses in this chaotic marketplace. Keep watching this space!

RECOMMENDED READINGS

The Supreme Court judgement dated 11thDecember 1996 in Writ Petition (Civil) No. 561 of 1994 (S. Jagannath v/s Union of India): https://main.sci.gov.in/jonew/judis/14622.pdf

The Coastal Aquaculture Authority (Amendment) Bill, 2023 text: https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/bills_parliament/2023/Coastal Aquaculture Authority (Amendment) Bill, 2023.pdf

The Parliamentary Standing Committee Report text: https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/bills_parliament/2023/SC_Report_Coastal_Aquaculture_Authority_(Amendment)_Bill,_2023.pdf